While browsing through an online museum exhibit, I came across an excerpt from this compelling article written during the internment of Japanese Americans in World War II. I managed to find a scan of the full article hosted by the UC Berkeley Library. The writer describes her family’s internment experience until their release in 1943, when the government decided to begin gradual release of those who had “defininite assurance of employment.”

“At first the crowd noise of 18,500 people jammed in together was so terrific that I thought I could never become accustomed to it. As the partitions between the stalls reached only a few feet, we could hear every sound made by neighboring families. It was a vast composite roar, an ocean of sound made up of talking people, crying babies, shouting voices, blaring radios, the tramping and shuffling of feet, and even more unpleasant noises.

…

Our visitors were usually tongue-tied and uneasy, in fact more embarrassed and ill at ease than we. They would stare at us with the saddest expressions in their eyes while their lips would try to murmur polite banalities. But, God bless them, we loved them—they gave us courage in our lowest moments.”

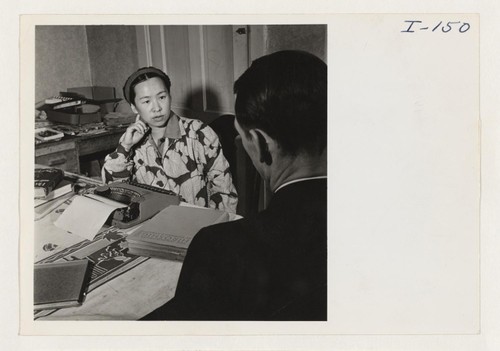

After some additional searching, I found the author in a 1944 photo, identified by her husband’s name, Mrs. Fred Mittwer. An article in Nichi Bei offers more biographical detail on the life Mary “Molly” Oyama Mittwer (her husband was the Tokyo-born son of a German father and Japanese mother).

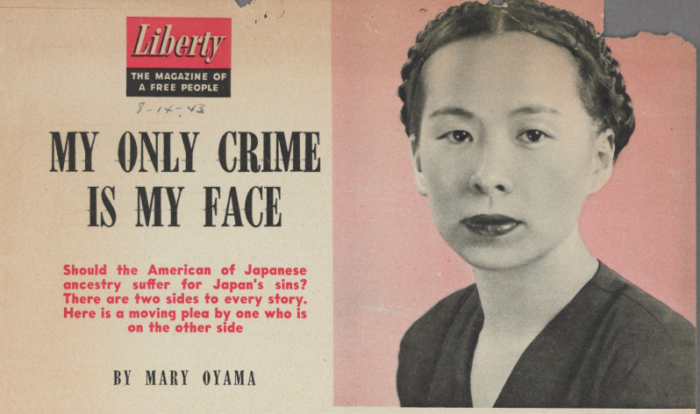

“Beyond causing her own exile and confinement, the wartime events left a powerful impact on Oyama Mittwer’s writing. First, Oyama Mittwer concentrated on bringing the plight of the Nisei to a larger readership and seeking help from outside allies. She published a pair of articles in Common Ground, a pro-immigrant quarterly founded by Louis Adamic. ‘After Pearl Harbor,’ which appeared in the spring 1942 issue, was a sketch of the misfortunes that the coming of war wrought on the Japanese community.

She followed up soon after with another article, “This Isn’t Japan,” an incisive sketch of conditions at Santa Anita. In November of 1942, she began a regular column, ‘Heart Mountain Breezes,’ in the Powell Tribune, a local weekly newspaper. In the wake of these articles, Oyama Mittwer was commissioned by the popular magazine Liberty (which had, ironically, been rabidly anti-Nisei in the prewar years) to write an article on the predicament of the Nisei. Her contribution, published in the fall of 1943 under the title ‘My Only Crime is My Face,’ was among the first writings by a West Coast Nisei to appear outside of the ethnic press. It pointed up the Americanism of the Nisei, and lamented the injustice of their confinement for ‘looking like the enemy.’

Meanwhile, Oyama Mittwer’s experience with official racism worked to sharpen her understanding of prejudice against other groups, and to push her to embrace interracial activism. As Oyama Mittwer later described it, the turning point was her house. In a poignant moment in ‘After Pearl Harbor,’ Oyama Mittwer had confided her worries that, unless her husband could find work, they might lose their beloved house. ‘I had thought it was only in old-fashioned melodramas that people lost their homes …’ Once ordered to leave the West Coast, the Mittwers were obliged to rent out their home in order to sustain it.

After they had interviewed several prospective tenants, a friend who worked with an Inter-Racial Fellowship asked whether they would be willing to rent to an African American couple. Oyama Mittwer later recounted her shock at the request. While she had never felt any racial prejudices, she also had next to no experience of blacks in her world. “We were so astonished by the novelty of the idea that we did a split-second mental flip-flop. But in that ‘end of a minute’ we did some fast thinking. ‘Negroes — er, ah. OK, gal you’ve always believed in democracy. Now’s your chance to do your stuff.’ So partly to our surprise we found ourselves saying casually, ‘Why, yes — send them up.’ The couple was the writer Chester Himes and his wife. Not only did the Mittwers agree to rent, their friendship immediately blossomed.

The result, Molly said, was that she ‘began to take an intense personal interest in the welfare of all Negro Americans.’ Himes was equally affected by his close friendship with Oyama Mittwer, and took an interest in the plight of Japanese Americans. In his novel ‘If He Hollers Let Him Go,’ Himes spoke of the affecting spectacle of ‘little Ricky Oyama’ singing ‘God Bless America’ as his family was being taken away. He also wrote an article about Japanese Americans for the interracial magazine The War Worker (for which Larry Tajiri would subsequently serve as a columnist).

…

Oyama Mittwer also threw herself into promoting progressive causes and fighting racism. In 1946 she was selected for the board of directors of the International Film and Radio Guild, an educational association designed to defend minorities from racial stereotyping, and she served alongside such luminaries as Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson and Lena Horne. Meanwhile, she led a letter-writing campaign to persuade Hollywood studios to make a film about Japanese Americans.”

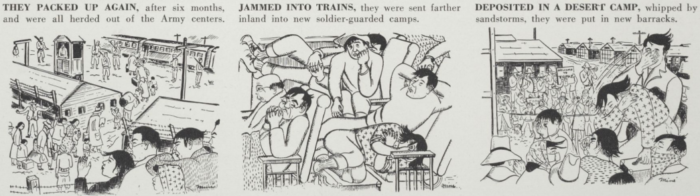

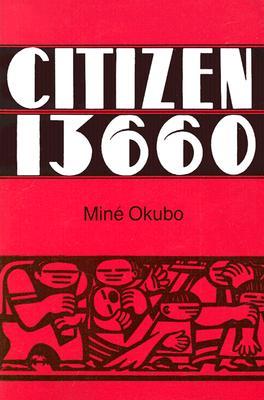

The scan from Liberty magazine also includes two more articles on the internment experience, as well as the drawings of Miné Okubo, who would go on to write the classic illustrated memoir Citizen 13660.