The dissolution of the Western Roman Empire is popularly perceived as a sudden and dramatic cataclysm, with the “fall of Rome” often precisely dated to 476 CE. In that year, so the story goes, the child Emperor of the West (later derisively referred to as Romulus Augustulus), was deposed by the barbarian warlord Odoacer who then established the first barbarian Kingdom of Italy. However, this familiar version of the fall of Rome can be charitably described as “incomplete.”

By 476 CE, the political power structures that underlay the Empire had long ago shifted to Constantinople, the capital of the largely Greek-speaking Eastern half of the Empire. Over a century earlier, Constantine I had effectively made the eponymous capital the center of the Roman political world. In 324 CE, when Constantinople was founded on the existing city of Byzantium, Constantine had just defeated his former ally, the pagan Eastern Emperor Licinius, becoming sole ruler of a united Empire.

Constantine’s victories in the civil wars of the Tetrarchy (against Maxentius in Rome and Licinius in the East) were contemporaneously viewed within a religious context. Though he favored Christianity over the old pantheon of the state, Constantine’s adoption of the Chi-Rho-adorned labarum (which would become the military standard of the late Empire) was inspired by his famous vision before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge rather than any devout adherence to existing Christian belief. Nevertheless, the end of the civil wars was perceived (and propagandized) as a spiritual triumph of Christianity and monotheism over the traditional gods of the state. After the collapse of the Roman political system in the Crisis of the Third Century, and its tenuous rebirth and regression to chaos in the civil wars, it must have been especially salient to see political stability finally return alongside the symbolic defeat of the one decrepit state institution that had so far survived—the old religion.

It’s important to note that Constantine and his cultishly-devoted soldiers believed in a world of many deities to whom competing interests could be appealed in order to win favor on the battlefield (a blend of religious exceptionalism and henotheism was the prevailing norm of the time). So unremarkable was this belief that the ostensibly pagan Licinius informed his troops not to lay eyes on Constantine’s labarum out of real fear that its magical power would curse them. Like Constantine, Licinius had previously had a divine vision of his own that presaged his victory in the Battle of Tzirallum against the Eastern Emperor Maximinus Daia.

Constantine himself simultaneously favored the Christian God and the sun deity Sol Invictus (popularized in the previous generation during the reign of Aurelian), perhaps seeing them as manifestations of the same supreme deity. It’s worth noting that the Arch of Constantine was positioned so that it aligned with Colossus Solis, the colossal statue of Sol Invictus that stood near the Colosseum (which derived its name from the statue). The dramatic shift in Roman semiotics that characterizes this period was undoubtedly facilitated by Constantine’s imposition of his own understanding of Christianity on the Roman political and military cultures.

Beyond the defeat of Licinius and the symbolic victory of Constantine’s pseudo-monotheism over the traditional pagan religion of the old Roman state, Constantine had other reasons to move the capital to Greece. Greek culture had shaped the adopted norms of Roman elites for centuries; it’s informative that Suetonius reported the then widely-held belief that the last utterance of Julius Caesar was the Greek phrase “καὶ σὺ, τέκνον” to his friend Marcus Junius Brutus, while Caesar’s famous “Commentāriī dē Bellō Gallicō” was explicitly made to further endear him to the masses. Thus, Constantine’s transfer of Roman central power to Greece represents a logical transition in the wake of decades of destructive in-fighting and the resultant decay of long-standing political institutions and networks in and around Rome itself.

While we’re on the subject of language, it’s worth noting that the word “pagan” derives from the Latin paganus, originally a descriptor used to identify rural people who lived outside of the empire’s bustling cities. Whatever negative connotations it had (like today’s country “bumpkin” or “redneck”) were amplified as Christianity was increasingly adopted throughout urban communities and among educated elites. That the term eventually came to refer simply to any non-Christian reveals the stark urban/rural cultural divide of the period, in which country people presumably held onto traditional polytheistic religious norms as the new Christian religion permeated burgeoning urban power networks in the post-Constantine empire.

These urban power networks—in Rome and in cities across the Empire—were destined to be dominated by the Christian Church. Internecine feuding among the various leaders of the nascent church throughout the Empire increasingly left Rome and its bishops (mostly members of the ancient families of the senatorial class) the vanguards of what would become Nicene Christianity. The city of Rome itself gradually became a merely symbolic if not spiritual capital. More often than not, ultimate political and military authority in the west would lay elsewhere; in what are now the cities of Milan, Trier, and Ravenna. For example, it was from Trier in Gaul that Valentinian I, the last Western Emperor who wasn’t a mere figurehead, ruled the West in the mid-to-late fourth century.

Thus, while the sack of Rome in 410 CE by Alaric and the Visigoths during the reign of the Western Emperor Honorius amounted to a humanitarian disaster for the city’s people, it was a symbolic defeat that, in and of itself, had little real impact on the political stability of the Empire as a whole even though it led to widespread consternation among Christians. Indeed, Augustine’s seminal work, The City of God, was a direct response to the spiritual misgivings that had swept through the Empire in the wake of the sack of Rome.

By then, the disastrous reign of Honorius (who became Western Emperor at the age of ten) had all but ensured that future Emperors in the West would be little more than puppets. The 400s were marked by the ascendency of de facto rule by the Magister Militum (“Master of Soldiers”) in the Western Empire, essentially the Emperor’s top general.

At this point, it’s worth emphasizing that the Roman armies of the West were increasingly populated by men who would have been perceived as only nominally Roman if not “barbarian.” The Magister Militum Flavius Stilicho, who held true power during the reign of Honorius, was himself the son of a Germanic Vandal and a provincial Roman woman. Indeed, military service had gradually become synonymous with barbarian identity, and the Roman soldiery was eventually comprised of a motley assortment of men of disparate ethnic backgrounds who came to speak a blend of Latin and Germanic languages distinctive to the Roman military. Trousers, long associated with “barbarians,” became widely adopted by Roman soldiers. Among them were “first-generation Romans” who came from migrant families that had only recently settled within the Empire or along its borders, as well as men whose families had considered themselves Roman for generations. It was largely this amalgam of military men, who often simultaneously held allegiance to the Roman state and to the various branches of Germanic tribes to which they belonged, that would ultimately come to gain complete political control of fragments of the Western Empire.

Odoacer provides an instructive example of the gradual shift towards “barbarian” military rule in the West. In fact, unlike the Visigothic “King” Alaric, Flavius Odoacer did not explicitly identify with any one tribe or group of people (his ethnic origin remains hotly debated). However, like Alaric, who was in fact a Roman military commander who served under the Eastern Emperor Theodosius before he rebelled and eventually attacked Rome, Odoacer too was a Roman military officer.

Shortly after the Eastern Emperor Zeno appointed Julius Nepos to be the Western Emperor in 474, Nepos was betrayed by his Magister Militum, a Roman aristocrat named Orestes who had come to notoriety as a secretary and envoy in the court of Atilla the Hun. The fact that Orestes chose to remain Magister Militum, instead proclaiming his young son Romulus Augustus the new Western Emperor, is an indication that the existing military establishment in the west viewed the imperial title as little more than ceremonial by this point (importantly, this was not the case in the east, where the Eastern Emperor was no figurehead).

Nevertheless, Nepos had escaped to Dalmatia, and Zeno refused to recognize Orestes or Romulus Augustus, considering them usurpers. It was in this context that the Roman officer Odoacer (who claimed no noble lineage), led the foederati (members of “barbarian” tribes from beyond the borders of the Empire proper who were bound by treaty to serve in the Roman military) to revolt against Orestes when he refused to cede to their demands for permanent land and housing within Italy. In fact, the largely Germanic foederati were joined by much of the standing Roman army (that is, ostensibly ethnic “Romans”).

When Odoacer defeated Orestes and deposed the usurper Romulus Augustus, he sent a senatorial delegation to Zeno to return the regalia of the Western Roman Emperor. Zeno bestowed Odoacer with Patrician rank, and granted him authority to rule Italy in the name of Julius Nepos. While Odoacer observed political niceties, officially ruling in the name of Nepos and Zeno, he never allowed Nepos to return to Italy.

Was Odoacer’s rise to power the end of Roman rule in Italy? What about the rest of the Western Empire? The better question to ask is: What would the people who lived in Western Europe have thought?

For the Romans who had survived the especially violent upheaval of the period (seemingly endless invasions, sieges, civil wars, famines, uprisings, lawlessness, and mass migrations), self-perceptions about political identity across continental Europe seemed to change little but for the fact that the small groups of men in power were foreigners who were no longer truly answerable to any Emperor. In some cases, the initial fiction of unbroken Roman political continuity in the West even included the minting of coins depicting the Eastern Emperor. Yet, while Germanic conquerors held political leadership, some portion of the bloated governmental bureaucracy that had developed across both halves of the Empire in the fourth and fifth centuries remained intact. The well-to-do continued to be educated in Latin and Greek, to study classical literature and philosophy, and aspired to bishoprics and governmental appointments (under Franks in Gaul or Visigoths in Spain). Roman populations under Germanic rule throughout Europe and the Mediterranean more or less remained Roman, and for the most part, so did their societies and cultures, at least in the beginning.

Despite popular perceptions that Romans were supplanted by Germanic populations, genetic evidence is finally settling the question of just how great the impact of barbarian migrations was on the demographics of the Western Europe that emerged from the carnage of late antiquity. It turns out that the answer is: Not very.1,2 It was only quite gradually (over hundreds of years) that the populations of Europe would come to see themselves as having socioculturally distinct ethnic identities synonymous with that of their conquerors rather than as being one pan-European “Roman” people. While the notion that there was ever a singular Roman identity may seem an oversimplification, it’s worth remembering that the cosmopolitan classical Empire had included a heterogeneous mix of peoples who were nevertheless united by a common subsuming Roman culture, so that ardent adherents of the very same mystery cults were as likely to be found in Britain as in Syria, to say nothing of the common worship of manifestations of the old Greco-Roman gods.

The Romans of Western Europe weren’t replaced; instead, over generations, they adopted the identities of their new masters. However, this was a transformation that went both ways, and Germanic peoples became Romanized to varying degrees, their original languages and traditions gradually fading away or transforming so as to be ultimately unrecognizable. This paved the way for the incubation of the distinct, nascent European cultures that would develop in the ensuing centuries.

On the other hand, it’s important to point out where this shift in identity didn’t happen, namely in the Eastern Roman Empire, where the people of the Greek-speaking world called themselves “Romans” (a term virtually synonymous with “Christian”) through the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and beyond. Although the seeds of a distinct pan-Greek identity were planted during the later years of the Eastern Empire, it came to full fruition as late as the 1800s during the movement for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire. Ironically, the Greek identity movement saw the revival of the classical hellenes ethnonym, a term which their Roman ancestors had derogatorily applied to small pockets of non-Christians in Greece during late antiquity and the middle ages.

Roman identity persisted elsewhere throughout Eastern Europe and the Middle East. The name of the country Romania essentially means “land of the Romans.” Writing in 1570, the Croatian Archbishop Antun Vrančić remarked on the people of Wallachia (at the time, an exonym used by outsiders to refer to a major region in Romania), “When they ask somebody whether they can speak Wallachian, they say: do you speak Roman? and [when they ask] whether one is Wallachian they say: are you Roman?” The Romagna region in Northern Italy is so named because it was controlled by the Eastern Roman Empire until the mid-8th century. The concept of a pan-Italian self-identity didn’t emerge until the 15th-18th centuries. Under Islamic rule, the people of what was formerly Roman Anatolia (modern day Turkey) initially came to identify their land with the Arabic word Rûm (Rome) and themselves as Rûmi (Roman).

The concept of “Roman” as an ethnic identity simply didn’t persist in Western Europe as it did in the East. The new Germanic “kingdoms” of Western Europe initially began with edicts and law codes that specifically distinguished between the Germanic ethnic group that conquered a given territory and the Roman subjects within (whose lives continued to be governed by the old Roman laws). For example, in Visigothic Spain, the law distinguished between romani and gothi until around 654 CE when the Lex Visigothorum abolished the distinction, recognizing all the kingdom’s people as hispani. During the reign of the Ostrogoths in Italy (discussed further below), intermarriage between Goths and Romans was explicitly outlawed. By the time the Germanic Lombards came to rule most of Italy, their Edictum Rothari in 643 CE (named for the Lombard King Rothari) continued to identify themselves as distinct from the Romans and therefore subject to different laws, but by the mid 8th century the legal distinction disappeared.

These cultural transformations were accompanied by truly staggering declines in civil infrastructure, technology, economic sophistication, and the dissemination of information. During the Roman Principate (the period that typically comes to mind when one thinks of “the Roman Empire,” stretching from the reign of Augustus to the Crisis of the Third Century), the European/Mediterranean economy reached heights that would be unequaled for another thousand years. This was largely facilitated by an infrastructure of ports and roads that were built, maintained, and secured by the Roman military.

By the fifth and sixth centuries, not only had this transportation infrastructure fallen into disrepair and banditry, it now spanned a patchwork of territories controlled by Germanic invaders and bands of what might have once been called Roman soldiers but who were now loyal to various competing warlords. The gradual loss of freedom of movement and travel was accompanied by declines in trade. This only further served to accelerate economic decline that had begun during the Crisis of the Third Century and the civil wars that followed.

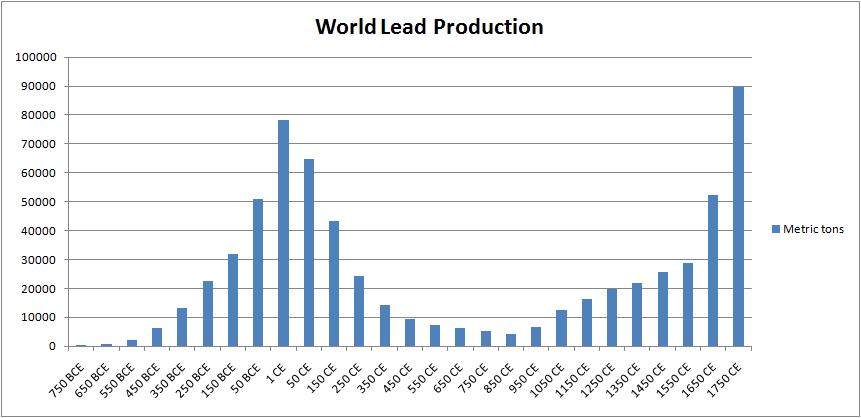

Greenland ice core data gives an indication of the level of global lead production, which closely tracks the fortunes of the Roman economy (see below).3 Amazingly, lead production levels would not surpass those of the Roman Principate until mere decades before the American Revolution. It’s worth noting that the period in which lead production bottoms out was a time in which the most powerful political leader of Western Europe—Charlemagne—was illiterate, scrupulously learning to read and write well into adulthood. Dark Ages indeed.

And what of the Italian peninsula after 476? Zeno ultimately sought to remove Odoacer from power, employing yet another group of foederati, this time a distinct tribe of Romanized Goths called the Ostrogoths. Their leader, Flavius Theodoricus (known to history as “Theoderic the Great”), had been made Magister Militum in Constantinople and even served as consul. After Zeno promised Theoderic control of Italy, the Ostrogoths invaded the peninsula and defeated Odoacer’s forces. A peace treaty negotiated by the bishop of Ravenna ensured that both Odoacer and Theoderic would have joint control of Italy. At a feast meant to celebrate the peace between them, Theoderic drew his sword and personally killed Odoacer in front of the gathering.

Just as Odoacer had done before him, Theoderic pledged to rule the lands of Italy in the name of Zeno, but his was less of an empty promise. The Roman political infrastructure that had existed before Odoacer’s revolt was largely restored including Roman legal codes, and Theoderic allowed free movement of people to and from the Eastern Empire. In return, the Eastern Emperor made the dramatic (albeit symbolic) gesture of sending the Western Imperial regalia to Theoderic, tacitly acknowledging him as Emperor of the West. Theoderic was eager to take the role, though never officially, instead retaining the pretense of subordination to the Eastern Emperor. Theoderic’s de facto reign was characterized by public works, rebuilding of infrastructure, and a deliberate effort to “restore” the symbols of power associated with principate Rome.

Nevertheless, continued tensions with the Eastern Imperial court would eventually spark war in 535, ten years after Theoderic’s death. The Eastern Emperor Justinian I sent his general Belisarius to lead a massive and costly campaign to finally regain proper direct political control of Italy and Rome, the namesake of both Empires and peoples. What followed was two decades of warfare that ravaged the Italian peninsula.

In order to finance 20 years of war, the Eastern Imperial court levied increasingly inordinate taxes on its populace. The war turned out to be a Faustian bargain for the East, driving many of its people to destroy their own buildings and property to avoid the ruinous tax burden, or to sell themselves and their family members into indentured servitude and debt bondage.

Although the Eastern Empire ultimately regained direct control of Rome and Italy, the Gothic War devastated the local population and infrastructure. Crucially, this period coincided with the Plague of Justinian, one of the deadliest pandemics in human history; the plague would ultimately claim the lives of an estimated 25 million people, or more than a tenth of the total global population.

Arguably more than any one event, it was this Justinianic Plague that was the death knell of the classical Roman world; a final, fatal blow against the already fractured civilization. If not for the devastation of the plague, Roman civilization and culture might have continued (perhaps even rebounded and flourished) under Germanic rulers and their assimilated peoples in much of Western Europe. Ostrogothic Italy provides a window into the stillborn beginnings of what might have been.

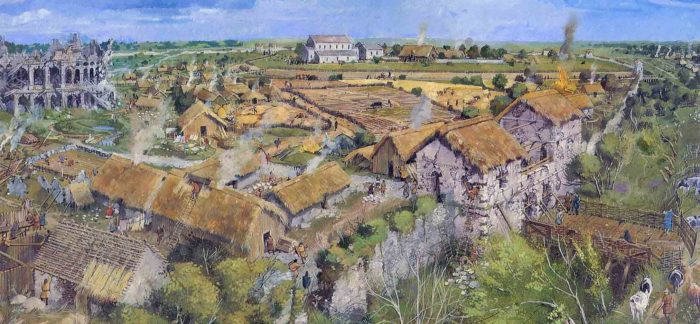

Yet by the time the pandemic finally subsided, the major Roman cities throughout the Empire and its former territories saw their populations bottom out. Abandoned infrastructure was now in decay, and ruined public buildings were adapted for any number of new utilitarian functions. The dissemination of specialized knowledge required to maintain the technology that underlay Roman urban life (e.g. indoor plumbing) had long ago largely ceased and eventually faded away. Once splendid villas now crumbled, becoming overgrown, dilapidated husks that dotted the countryside.

By the middle of the sixth century, Rome was a largely empty city of abandoned and ruined buildings. Constantinople didn’t fare much better, with nearly half of its population wiped out.

Though the Roman Empire had withstood the Antonine Plague in the second century, a pandemic that claimed as many as 5 million lives including much of the Roman military, that outbreak had taken place at the zenith of Roman power. The Antonine Plague may have paved the way for the Crisis of the Third Century roughly fifty years later (during which yet another plague unfolded, the Plague of Cyprian). Thus, pandemics had the potential to shake the foundations of even a thriving empire.

Not only was the empire not thriving in the sixth century, it was undergoing total collapse and dismemberment. Beyond Italy, Britain had been long-abandoned by the central Roman state, and all of western Europe had been carved into various territories in which self-styled kings and their marauders ruled local populations (e.g. the Gallo-Romans were ruled by the Franks, the Hispano-Romans were ruled by the Visigoths). In some cases, these territories had been taken over by bands of soldiers who had simply been billeted in the region by the Roman state. Although Roman ways of life ostensibly continued but for the change in management, Britain was a different story; archaeological evidence shows a dramatic and rapid decline in the level of technological sophistication there, a process that would unfold more gradually (and less completely) throughout continental Europe.

If any part of the Empire could fairly be described as experiencing the fall of civilization, it was in Roman Britain. Indeed, the desperate state of affairs in Britain may have made the Roman population there especially susceptible to the Justinianic Plague, which further depopulated the island and may have facilitated its conquest and settlement by the diverse Germanic peoples who would come to be called the Anglo-Saxons. In this case too, new genetic evidence is finally overturning the long-held perception that Germanic foreigners completely replaced local Roman populations. Rather than experiencing a massive influx of Anglo-Saxons, it seems that Britain was conquered by relatively small bands of invaders. As was the case in continental Europe, these people have left little genetic imprint on the population.4,5,6 Despite notions long-cherished by some, the idea that the English have a common Anglo-Saxon origin is a myth that has now been conclusively upended by genetic evidence.

Although Rome itself would remain under the control of the Eastern Empire for the next two centuries, the end of the Gothic Wars, the Plague of Justinian, and the subsequent invasion of Italy by the Langobards (better known as the “Lombards”) marked the completion of the gradual destruction of the Western Roman Empire, the ultimate collapse of classical civilization, and the transition into a new Medieval world.

Yet, even though Medieval Europe and classical Roman civilization of the principate (the 1st-3rd centuries) would surely seem mutually alien to people native to each but transplanted across time, the people of the Middle Ages retained more than a patina of cultural continuity with the old civilization, living as they were within its dusty skeleton. The revival of the Western Imperial title, bestowed by Pope Leo III to Charlemagne in 800, offers some sense of the value Medieval aristocracy placed in the pretense of political continuity with Roman civilization. It’s worth noting that the Frankish kingdom Charlemagne ruled, known to historians as the Carolingian Empire, had been known to its own people as Romanorum sive Francorum imperium, the “Empire of the Romans and Franks,” or simply Romanum imperium.

Epilogue

◊

Charlemagne’s title as “Emperor of the Romans” was revived in 962, with the Germanic Romanum imperium evolving into the patchwork of territories that came to be called the Holy Roman Empire by the 13th century. The Empire lasted until 1806 when it was dissolved by Napoleon. Although the Eastern Roman Empire would come to be known as the Byzantine Empire, this is a relatively modern historiographical invention; as previously mentioned, despite the fact that Greek was their lingua franca, the people of the Eastern Roman Empire referred to themselves as Romans and called their empire the “Roman Empire.” The Eastern Roman Empire would go on to face invasions by both Christian Crusaders from the west and Muslim warriors from the east and south, ultimately coming to an end with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans and the death of the last Eastern Roman Emperor in 1453. The Ottoman leader, Sultan Mehmed II, claimed the title “Qayser-i Rûm” (Caesar of the Roman Empire), and portrayed the Ottoman state as a direct continuation of the Roman Empire. It’s worth noting that at its zenith, the Ottoman Empire’s territory roughly coincided with that of the Eastern Roman Empire. Constantinople was renamed Istanbul and became the Ottoman capital until the Empire’s dissolution in the 20th century following World War I and the rise of the Young Turks.

[1] Amorim CEG, Vai S, Posth C, et al. Understanding 6th-Century Barbarian Social Organization and Migration through Paleogenomics. 2018. doi:10.1101/268250.

[2] Ralph P, Coop G. The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe. PLoS Biology. 2013;11(5). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555.

[3] Greenland Ice Core Evidence of Hemispheric Lead Pollution Two Millennia Ago by Greek and Roman Civilizations, Hong. S. et al., Science, vol. 265, 23 September 1994, page 1842.

[4] Töpf AL, Gilbert MTP, Dumbacher JP, Hoelzel AR. Tracing the Phylogeography of Human Populations in Britain Based on 4th–11th Century mtDNA Genotypes. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;23(1):152-161. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj013.

[5] Schiffels S, Haak W, Paajanen P, et al. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10408.

[6] Sayer D. Why the idea that the English have a common Anglo-Saxon origin is a myth. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-the-idea-that-the-english-have-a-common-anglo-saxon-origin-is-a-myth-88272. Published April 26, 2018. Accessed April 28, 2018.