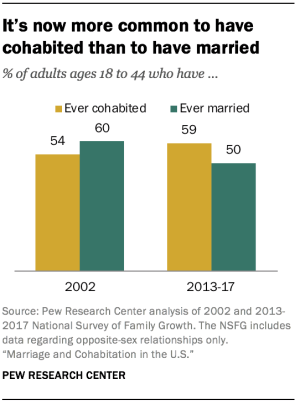

Recently released data from Pew’s American Trends Panel survey confirm that American attitudes toward marriage are undergoing a steady but seismic shift. By 2017, only 50% of Americans ages 18-44 had ever been married.

Recently released data from Pew’s American Trends Panel survey confirm that American attitudes toward marriage are undergoing a steady but seismic shift. By 2017, only 50% of Americans ages 18-44 had ever been married.

There are marked generational differences on the question of whether long-term cohabiters should ultimately marry; 55% of those ages 18-29 agree that it is “just as well” for long-term cohabiting couples never to marry whereas only 35% of those aged 65+ agree. It seems clear that this reflects durable cohort effects and not age per se. That is, we can expect that as the years go by, a majority of Millennials will continue to be indifferent about whether cohabiters should decide to marry or not.

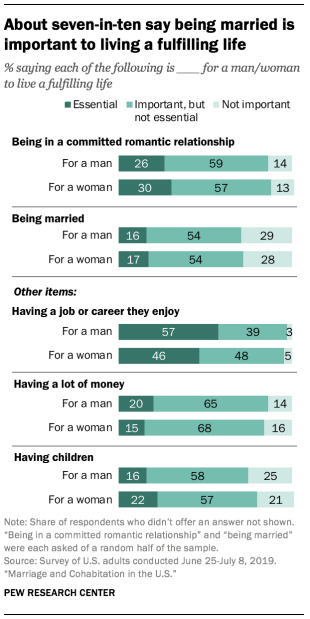

Perhaps unsurprisingly, only a minority of respondents said that being married was essential to live a fulfilling life. Unfortunately, we’re not given a breakdown by age group, but it seems a safe bet that these small numbers are largely pulled upward by older adults. I imagine that the percentages are considerably lower for e.g. ages 18-29.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, only a minority of respondents said that being married was essential to live a fulfilling life. Unfortunately, we’re not given a breakdown by age group, but it seems a safe bet that these small numbers are largely pulled upward by older adults. I imagine that the percentages are considerably lower for e.g. ages 18-29.

While only 14% of men and 13% of women agreed that being in a committed romantic relationship is “not important” to live a fulfilling life, the numbers who said the same about being married are more than twice as much (29% and 28% for men and women respectively).

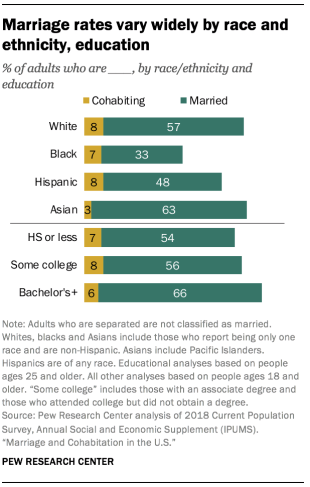

So as attitudes change, what about the broader picture regarding marriage? Penn Wharton Budget Model’s 2016 analysis of socioeconomic patterns of marriage and divorce remains a worthwhile primer on the growing marriage class divide. Marriage is increasingly becoming a “luxury good,” and “more intensely assortative — the inclination to marry a similar partner — especially with respect to those with college degrees and high education levels,” a trend facilitated by modern dating platforms such as OKCupid and Tinder.

The growing marriage divide is confirmed by this latest Pew data, which shows sizable racial and educational gaps in marriage rates.

As we transition from a society where marriage was the expected norm (regardless of income level), desirable potential spouses are increasingly those who have the right assets. An article by Philip Cohen highlights the ways in which this shift has left historically disadvantaged groups behind:

As we transition from a society where marriage was the expected norm (regardless of income level), desirable potential spouses are increasingly those who have the right assets. An article by Philip Cohen highlights the ways in which this shift has left historically disadvantaged groups behind:

“One critique of the marriage promotion movement is that it ignores the problem of available spouses, especially for Black women. …it’s increasingly the most well off who are getting and staying married, and those who aren’t marrying may not have the assets that lead to marriage benefits: skills, wealth, social networks…”

This provides a good segue to:

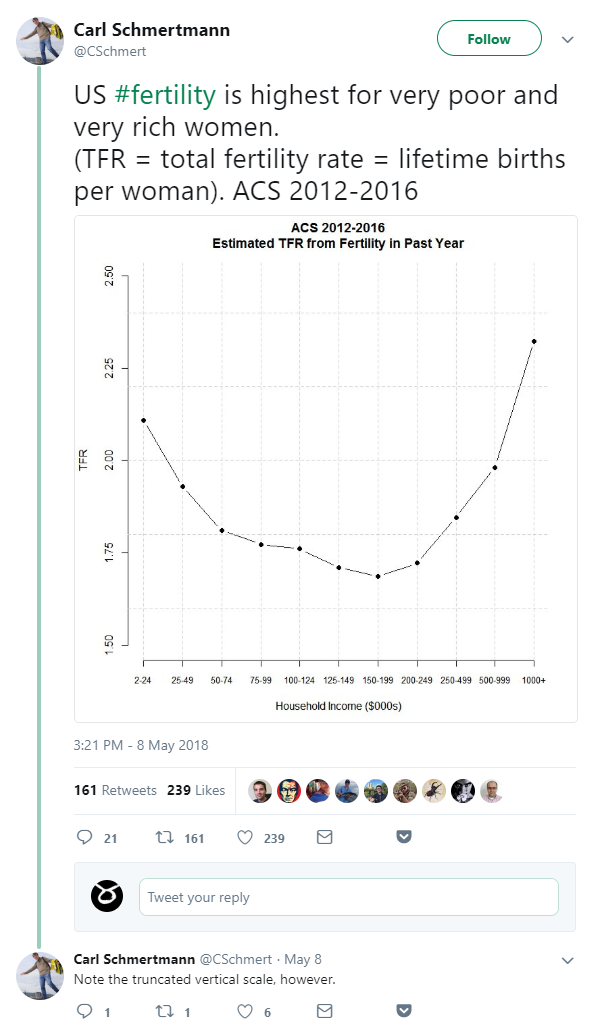

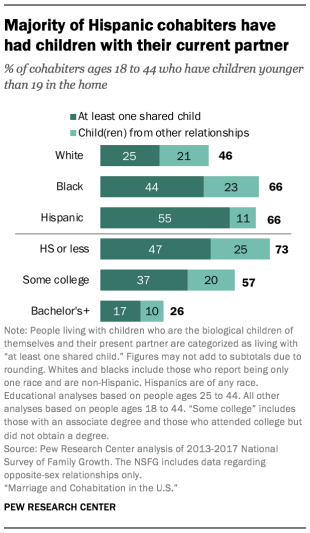

While the very wealthy and very poor have the highest fertility rates, the wealthy are much more likely to be raising their children within the context of a marriage. Again, this is corroborated by the Pew data on cohabiters who have children. Note the rather extreme racial and educational disparities.

While the very wealthy and very poor have the highest fertility rates, the wealthy are much more likely to be raising their children within the context of a marriage. Again, this is corroborated by the Pew data on cohabiters who have children. Note the rather extreme racial and educational disparities.

Assortative mating is also exacerbating income inequality. While plenty has been published on the topic, this classic 2014 paper by Greenwood et al spells it out pretty plainly:

“…if matching in 2005 between husbands and wives had been random, instead of the pattern observed in the data, then the Gini coefficient would have fallen from the observed 0.43 to 0.34, so that income inequality would be smaller. Thus, assortative mating is important for income inequality.”

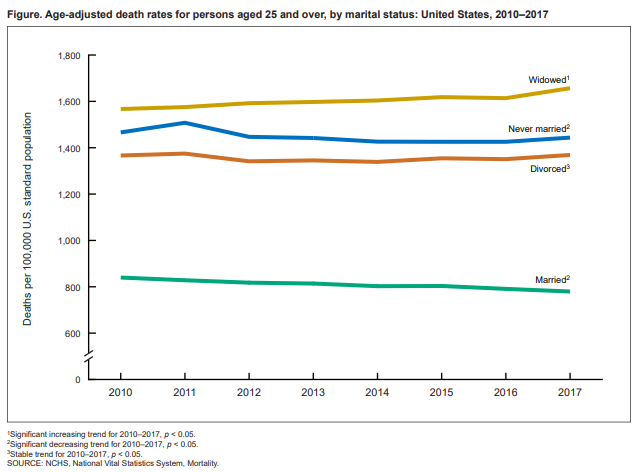

There’s good reason to believe that assortative mating may also drive inequalities in long-term health outcomes. Just last month, the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics released its first report on death rates by marital status in nearly 50 years. The magnitude of the difference in death rates between married and never married adults is pretty astounding.

Note that while death rates for every other group either increased or mostly stayed the same between 2010-2017, the gap actually widened for married adults; their death rate declined by a whopping 7%. The effect is as pronounced for women as it is for men: in 2017, the death rate for married women was nearly half that of never married women (569.3 vs 1,165.6 respectively, per 100,000).

While there’s no doubt that these numbers are influenced by an underlying selection effect (people who are healthier to begin with are likely to be more desirable partners), there’s also no doubt that marriage per se is protective. As lead author Sally Curtin says, “married people are more likely to have health insurance, and a spouse may encourage better lifestyle and health habits as well as assist in healthcare related activities (scheduling doctor’s appointments, etc…).” It’s not difficult to think of countless other ways marriage could bring tangible health benefits along with expansion of an individual’s safety net. Marriage a “luxury good” indeed.

Despite these fairly stark numbers, the notion that marriage provides benefits to health and well-being is often scoffed at in new media and pop literature. Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas, science director of UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, offers a nuanced and thoughtful perspective on the issue. While acknowledging the harm that bad marriages can do, and that people generally lack preparedness for the kind of commitment and patience a good marriage requires, she’s nevertheless straightforward about the potential benefits:

“Altogether, decades of research from human development, psychology, neuroscience, and medicine irrefutably converge on this conclusion: Being in a long-term, committed relationship that offers reliable support, opportunities to be supportive, and a social context for meaningful shared experiences over time is definitely good for your well-being.”

None of this is intended to gloss over the fact that marriage has traditionally been used to impose and maintain gender inequities, or any of the countless negative effects of loveless, joyless, or abusive marriages. Likewise, there are countless virtues to being single, especially when it comes to being able to fully form your own unique identity, to achieve lasting, fulfilling self-acceptance. I don’t presume to know what any specific person should or shouldn’t do. Rather, my interest here is mostly in exploring the broader societal effects of shifting marriage trends.

It’s clear to me that happiness is fundamentally ephemeral. Assuming that it can be a permanent state, and using it to anchor yourself to another human being is not necessarily going to lead to true fulfillment. Yet I have no qualms about saying that I emphatically agree with the quote above from Simon-Thomas. There’s no doubt that a good marriage can be very good for long-term well-being. So if marriage is not necessarily about everlasting happiness, what is it about? I’ll close here with a refreshing and very worthwhile take on marriage by Nate Bagley (referencing the excellent work of Eli Finkel): Seriously. What’s the Point of Marriage?

“But this is what love is really about. It is not always about always pleasing your partner, or always being pleased yourself. Instead, it is about supporting your partner.

… Supporting your partner means you have their best interests at heart and you intentionally act to uphold and achieve those interests. It means you stand by their side, you help them, you have their back, and sometimes it means you engage in conflict about difficult truths and regrettable incidents. True partners dedicate themselves to the person they love and to the bond they share, even when those acts of dedication might be temporarily painful due to the positive growth it causes.

Dedication to that positive growth forces you to identify and open up about your weaknesses, insecurities, and fears is exactly what leads to the periods of happiness, trust, connection, passion, and commitment.”