Scivias by Hildegard of Bingen

Scivias by Hildegard of Bingen

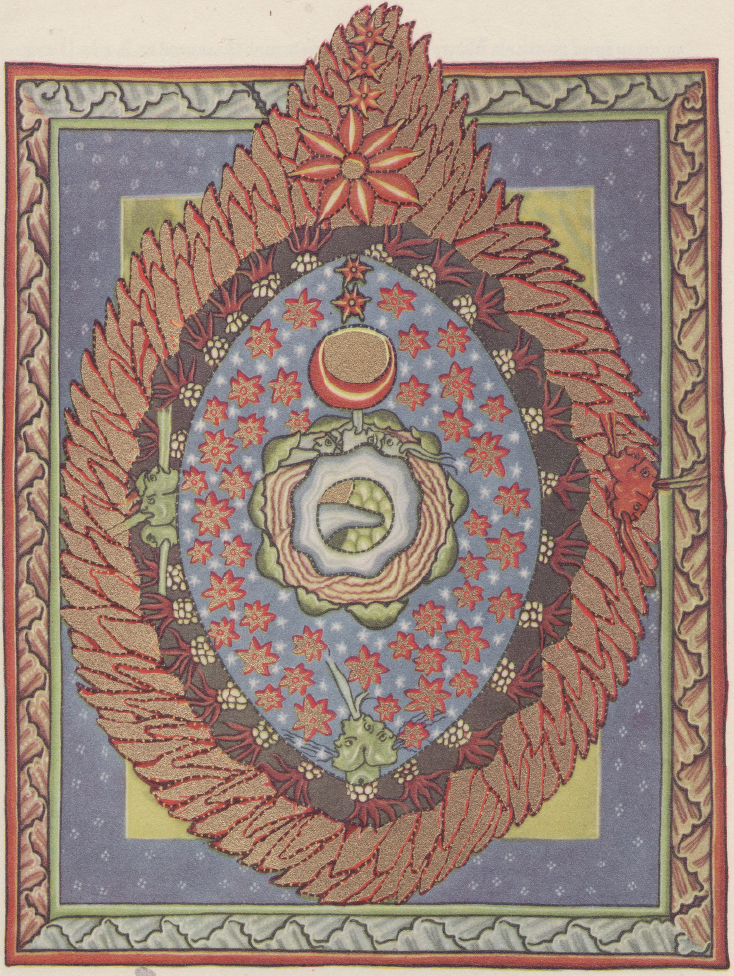

Hildegard von Bingen’s Scivias (short for “Scito vias Domini,” or “Know the Ways of the Lord”) is, as the title suggests, mostly comprised of various divinely-ordained rules for life, with an emphasis on potential social deviancy. In a manner reminiscent of the Book of Revelation (or even the Quran), Hildegard describes a particular vision (remarkable for their unusually abstract nature), and then recounts the words of God’s direct speech explaining the meanings of each vision to Hildegard. This is especially fascinating since I’m not aware of similarly lengthy medieval texts purported to contain God’s direct speech that were accepted by both Papal and political authority. Her visions are depicted by illuminations (the making of which she oversaw) that are arguably some of the most beautiful and haunting art to be produced anywhere in Europe during this period (~1150 CE).

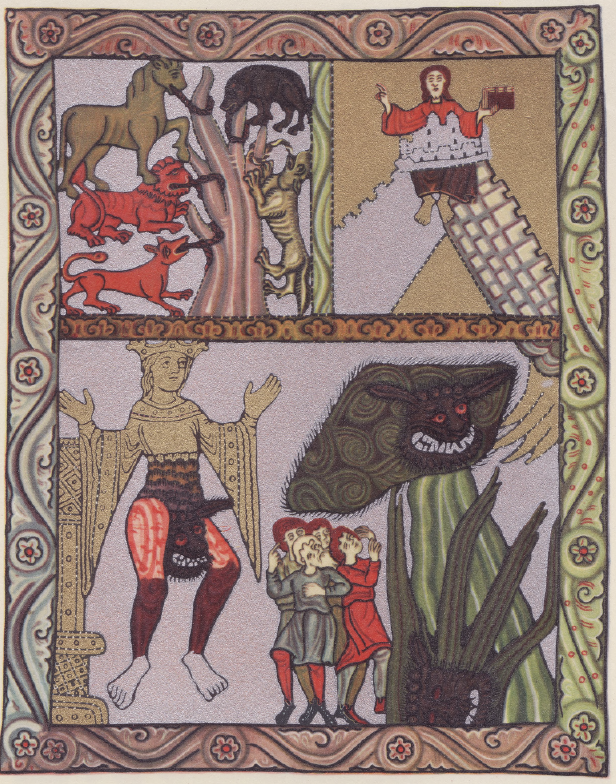

The images below are from a 1954 German language edition in which the only surviving Liber Scivias facsimile was reproduced in full.

To give a sense of Hildegard’s visions, here is the text accompanying Vision 1: “I saw a great mountain the color of iron, and enthroned on it One of such great glory that it blinded my sight. On each side of him there extended a soft shadow, like a wing of wondrous breadth and length. Before him, at the foot of the mountain, stood an image full of eyes on all sides, in which, because of those eyes, I could discern no human form. In front of this image stood another, a child wearing a tunic of subdued color but white shoes, upon whose head such glory descended from the One enthroned upon that mountain that I could not look at its face. But from the One who sat enthroned upon that mountain many living sparks sprang forth, which flew very sweetly around the images. Also, I perceived in this mountain many little windows, in which appeared human heads, some of subdued colors and some white.”

This vision is just the first introduction to what are purported to be God’s insights, transmitted to Hildegard through especially esoteric and often jarring visual symbolism. Hildegard’s theological exegesis unfolds in numbered lists that follow each vision; after a brief recounting of Lucifer’s fall, an affirmation of the reality of damnation (the pre-King James “Gehenna,” distinct from modern popular conceptions of “hell”), and original sin (“Because [the Devil] knew that the susceptibility of the woman would be more easily conquered than the strength of the man; and he saw that Adam burned so vehemently in his holy love for Eve that if he, the Devil, conquered Eve, Adam would do whatever she said to him.”), Hildegard deftly transitions directly from Eve’s transgression in Eden to “What things are to be observed and avoided in marriage.”

In proscribing specific behaviors, there is (unsurprisingly) a particular focus on sexual intercourse, marriage, and proper gender roles. For example, Book I. Vision 2.22: Those who have intercourse with the pregnant are murderers. “…The woman is subject to the man in that he sows his seed in her, as he works the earth to make it bear fruit. Does a man work the earth that it may bring forth thorns and thistles? Never, but that it may give worthy fruit. So also this endeavor should be for the love of children and not for the wantonness of lust. Therefore, O humans, weep and howl to your God, Whom you so often despise in your sinning, when you sow your seed in the worst fornication and thereby become not only fornicators but murderers; for you cast aside the mirror of God and sate your lust at will.”

God forbids women from the priesthood: Book II. Vision 6.76: Women should not approach the office of the altar. “So too those of female sex should not approach the office of My altar; for they are an infirm and weak habitation, appointed to bear children and diligently nurture them. A woman conceives a child not by herself but through a man, as the ground is plowed not by itself but by a farmer…”

In another illustrative example, God forbids straying from gender restrictions on clothing; Book II. Vision 6.77: Men and women should not wear each other’s clothes except in necessity. “A man should never put on feminine dress or a woman use male attire, so that their roles may remain distinct, the man displaying manly strength and the woman womanly weakness; for this was so ordered by Me when the human race began. Unless a man’s life or a woman’s chastity is in danger; in such an hour a man may change his dress for a woman’s or a woman for a man’s, if they do it humbly in fear of death. And when they seek My mercy for this deed they shall find it, because they did it not in boldness but in danger of their safety, But as a woman should not wear a man’s clothes, she should also not approach the office of My altar, for she should not take on a masculine role either in her hair or in her attire.” Hildegard’s words on this subject aren’t trivial: nearly 300 years later, the only heresy charge for which Joan of Arc would be convicted was cross-dressing. It was enough to warrant her being burned alive.

Most of the text reads like this, though Hildegard (through what are purportedly God’s direct words) also seeks to expound and justify existing church doctrine, as well as to address apparent contradictions. This is aided by judicious use of excerpts from the Old Testament.

Hildegard’s final vision is prophetic rather than prescriptive: The church is depicted as a woman (the bride of God), and interestingly, the antichrist is depicted as a monstrous face where the woman’s genitalia should be. Book II. Vision 11. The Last Days and the Fall of the Antichrist: “…And I saw again the figure of a woman whom I had previously seen in front of the altar that stands before the eyes of God; she stood in the same place, but now I saw her from the waist down. And from her waist to the place that denotes the female, she had various scaly blemishes; and in that latter place was a black and monstrous head. It had fiery eyes, and ears like an ass’, and nostrils and mouth like a lion’s; it opened wide its jowls and terribly clashed its horrible iron-colored teeth.”

Also, Book II. Vision 11.14 Antichrist will horribly rend the faithful and cruelly tear humanity. “And thus in the place where the female is recognized is a black and monstrous head. For the son of perdition will come raging with the arts he first used to seduce, in monstrous shamefulness and blackest wickedness. It has fiery eyes, and ears like an ass’, and nostrils and mouth like a lion’s; for he runs wild in acts of vile lust and shameful blasphemy, causing people to deny God and tainting their minds and tearing the Church with the greed of rapine. It opens wide its jowls and terribly clashes its horrible iron-colored teeth; for with his voracious and gaping jaws he evilly infuses those who consent to him with his strong vices and mordant madness.”

Recent decades have seen a resurgence of popular interest in Hildegard von Bingen, perhaps due mostly to the modern New Age movement. I humbly suggest that anyone who thinks Hildegard’s brand of mysticism fits neatly into the New Age pastiche might be disabused of this notion if they took the time to read Hildegard’s actual literary works written in her own words.

Recent decades have seen a resurgence of popular interest in Hildegard von Bingen, perhaps due mostly to the modern New Age movement. I humbly suggest that anyone who thinks Hildegard’s brand of mysticism fits neatly into the New Age pastiche might be disabused of this notion if they took the time to read Hildegard’s actual literary works written in her own words.

Hildegard was a woman who was arguably one of the most creative and productive intellectuals of her time (her creative output includes decades’ worth of books, letters, poems, and songs), a period in which a deeply, unabashedly patriarchal society held women to be something almost less than human. Yet, whatever her value as an inspirational feminist figure, those looking for an anti-patriarchal hero will find little to admire in Hildegard’s plainly abhorrent and backward views of women and gender roles. Like almost everyone that’s ever lived, she was a person firmly embedded in the culture of her time and place.

When appreciated for historical insight, when taken on her terms rather than ours, the value of Hildegard’s work remains for those interested in the past. They’ll find that, beyond the beautiful, hypnotic illuminations, Scivias offers a relatively concise and readable glimpse into the prevailing cultural and spiritual values of medieval Western Europe.